The future of hydrogen at sea

The thought of a vehicle fleet whose only residual product is water has made hydrogen one alternative in the hunt for tomorrow’s fossil-free fuel. But hydrogen needs a tank five to ten times bigger than today’s, and its production is not yet entirely climate smart.

Right now, many different ways to achieve more sustainable maritime shipping are being tested. We’ve written previously about E-methanol, wind power and LNG, and now it’s the turn of hydrogen.

Hydrogen used as fuel is more efficient than liquid fuels and generally involves no emissions other than pure water vapour. By using hydrogen together with fuel-cell motors, you’ll be sparing the environment from harmful emissions of carbon dioxide, particulates and NOx.

“There are challenges associated with using hydrogen on a large scale, but no truly impossible problems. How to produce renewable hydrogen will require some thought, as will how to store and transfer the quantities needed,” says Maria Grahn, who has spent a lot of time studying the advantages and disadvantages of hydrogen in her capacity as a research scientist at the Department of Mechanics and Maritime Sciences at Chalmers University of Technology.

Complex storage and distribution

Hydrogen is already used as a fuel today in a small number of vessels, but it will take time before renewable hydrogen in large quantities is available for purchase in ports. The toughest nuts to crack will be the actual storage and distribution.

“In fact, you need a tank five times as large to hold enough liquid hydrogen to get as far as diesel or bunker oil will take you. And for hydrogen as a compressed gas, the tank needs to be 10 times the size,” informs Maria.

And before the ship can take hydrogen on board it must first be moved out of production and into port, not a particularly easy manoeuvre and depending on the method, one which can impact both the environmental gains and the wallet. Compressed hydrogen gas can be distributed in pressure vessels loaded on trains or trucks or via pipeline. According to the studies conducted by Maria, the latter alternative is the least expensive but the disadvantage is a tendency to form leaks. Hydrogen in liquid form is easier to handle, but it must be cooled down to minus 253 degrees.

“It takes quite a lot of energy to reach such low temperatures. In fact, as much as one third of the energy in hydrogen gas is expended on keeping it liquid,” says Maria.

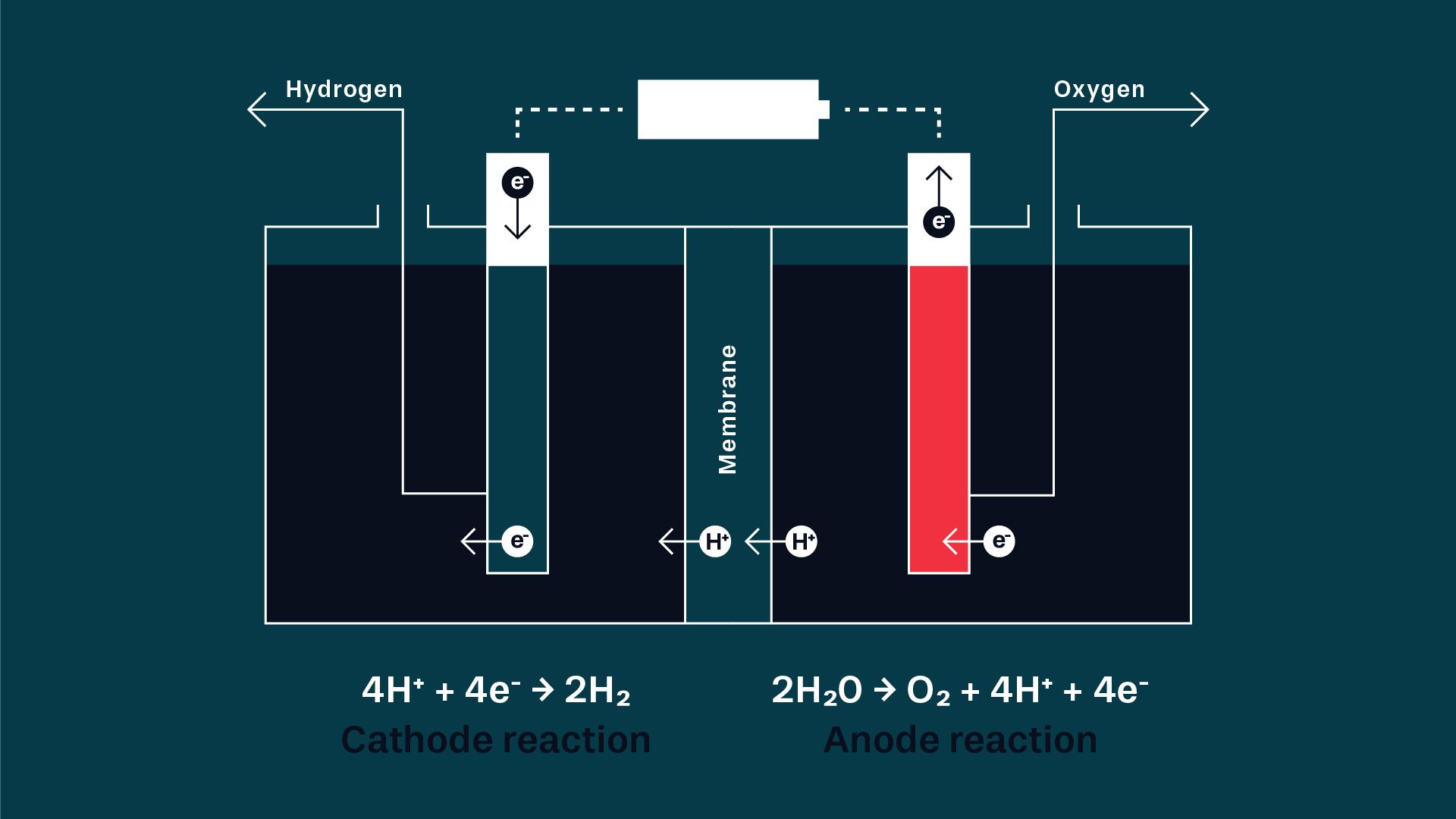

Steam reforming or electrolysis

Hydrogen is one of Earth’s most common elements, and is usually found bound up in water. It must be released in one way or another in order to use it as an energy source, and the way this is done has a great impact on just how climate smart the end product is.

“One of the major advantages of hydrogen is our ability to produce it in so many different ways, but today most hydrogen is produced by steam reforming natural gas, a fossil energy source. There are climate-smart techniques for doing this and for capturing the carbon dioxide, but the most studied method for the future is electrolysis, where we use renewable electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. This method is a little more expensive, but fossil-free,” says Maria.

Future prospects

In the DNV GL Maritime Report to 2050, hydrogen gas is predicted to have limited importance as ship fuel because of the high fuel price, its low energy density and the challenges concerning storage and handling. Maria Grahn, who is involved in multiple research projects looking into new ways to exploit hydrogen gas, believes in hydrogen, but in combination with other fuels.

“I’m convinced there will be many different alternatives in which hydrogen will play an important part. But I don’t believe we’ll be running container ships over long distances fuelled by hydrogen, but rather vessels that ply shorter routes. The important thing is not to lock ourselves into a single technology, but to leave the door open to other solutions and see what is best for each individual vessel and route.”

In Addition

The risks with hydrogen

There are currently no comprehensive rules and regulations for handling hydrogen as a fuel for maritime shipping, and there is only limited experience. DNV GL is actively engaged in increasing knowledge and experience within this field. According to Mikael Johansson, Principal Consultant at DNV GL, there are risks to consider.

Fire & explosion risk: Hydrogen is flammable with a fuel/air mixture of 4–75%, and is explosive between 18–59%. Also, hydrogen fires are difficult to detect as the flames are invisible. Furthermore, liquid hydrogen expands violently in the case of leaks and can result in an explosive course of events without the gas igniting.

Cold: In liquid form, hydrogen is 253 degrees below zero. Handling a liquid this cold constitutes a direct hazard to people engaged in fuelling or onboard a ship, and the cold will also freeze most materials and be a hazard even from this perspective. What’s more, the low temperature means that the liquid itself may freeze e.g. air or oxygen and block pipework systems.

Health and environmental hazards: Hydrogen is not usually toxic for people or the environment and does not affect the atmosphere. But a leak in a confined space can lead to suffocation if the gas does not ignite beforehand.

Effects on materials: Due to the extremely small size of the hydrogen molecule, leaks are especially difficult to handle and may also impact the strength of certain materials in what is known as hydrogen embrittlement.